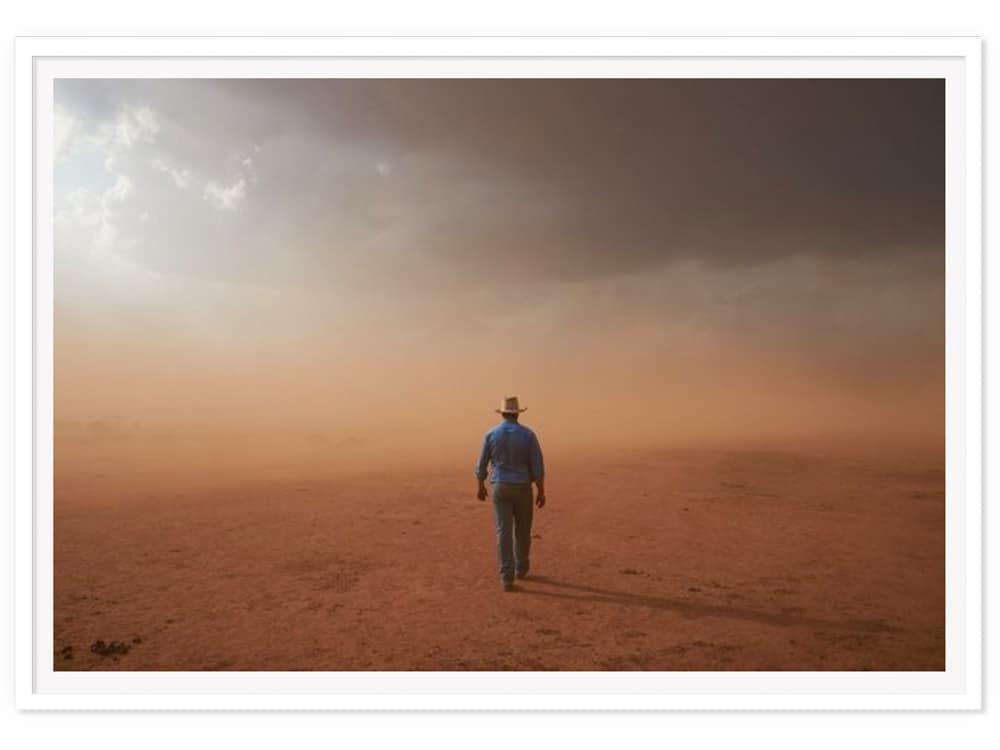

A Farmer is shown walking his land – the air so thick with dust, the line between sky and earth is completely lost. He’s dressed in blue, a strong contrast to the reds and greys of the world around him, and there’s something about his stance that speaks to strength or maybe resignation. This is Drought Story, by photographer Joel B Pratley, the winner of the 2021 National Photographic Portrait Prize.

The man in the photograph is farmer David Kalisch. Pratley met him while working on a campaign for the charity Rural Aid, which aimed to drive donations to famers in need by showing how different farms were trying to survive the drought.

“We were down there and photographing them and their day-to-day routines – feeding sheep and cattle and just trying to kind of do chores in a really desolate backdrop,” Pratley explains. Then they were hit by a massive dust storm. The thing that struck Pratley as he photographed through it was that “David, the farmer, was very stoic and not really shaken, because he just got so used to them. It took our reaction to remind him that, hey, this is not a very nice new normal.”

Pratley uses his photography to tell stories that might otherwise not get attention. “I always try to look for an image that is bigger than me, bigger than the person that’s in it, that has a really important theme or message that a lot of people can connect and resonate with.”

In his work he focuses on storytelling, in particular, telling the stories of those whose lives have been shaped by circumstances outside of their control. He traces this interest in people, in stories, back to his own childhood. “I spent a bit of my life growing up in social housing with my single mum, and part of my life growing up with my grandparents. I have a really soft spot for the elderly and people who are a bit more downtrodden,” he says.

After working a series of “dead-end jobs in my late teens and early twenties” Pratley saved up enough money for a backpacking trip for nine months. “Big cliché,” he says with a laugh, but after he returned he knew that photography was what he wanted to do, and got a job working as a photographer’s assistant and slowly worked his way up from there.

“When I first started I was kind of doing a little bit of everything, but now I really work on making sure that the jobs I get suit me – I really like working with everyday people,” he reflects. In between jobs, for the past two years he has been working on a project called “Greetings From Waterloo”, looking at the impact of gentrification in the inner-city suburb. “It’s a big social housing area,” he explains, and so for him the rapid gentrification has raised many questions for us as a society. “Who has the right to live there? What freedoms do they have as individuals – and what lives have people built there?”

Drought Story ties back to his ethos of shining light on individual lives, on individual struggles – and winning the National Photographic Portrait Prize has helped put this story on the national stage. Though Pratley was proud of the picture, he never expected to take out the prize. “To be a finalist it’s already a pretty big win – I’ve been a finalist a few times and that’s fantastic but to actually take out the prize, I was astounded.”

He gave some of the prize money to Kalisch. “Portraits involve two people, you know, not just a photographer – there’s someone that’s given their time and opened up as well. So I think it’s important to remember that,” he says. Recently he had a chance to go back and visit. “I was able to go back there and stay the night on their farm and have dinner with them and chat. It’s kind of really cool that photography for me can do that, gives me an excuse to make friends. Maybe that’s something I had trouble with when I was younger,” he says.

During the dust storm, Pratley took a lot of photos, but the one he ended up submitting to the prize was the obvious choice for him. “What really kind of struck me about that one is it kind of had a real symbolic and spiritual presence,” he reflects. “I just think humans, we march off into the great unknown a lot of the time – and there’s a little glimmer of hope there; there’s a little bit of a break in the clouds.”

This article was produced by Broadsheet in partnership with the National Portrait Gallery